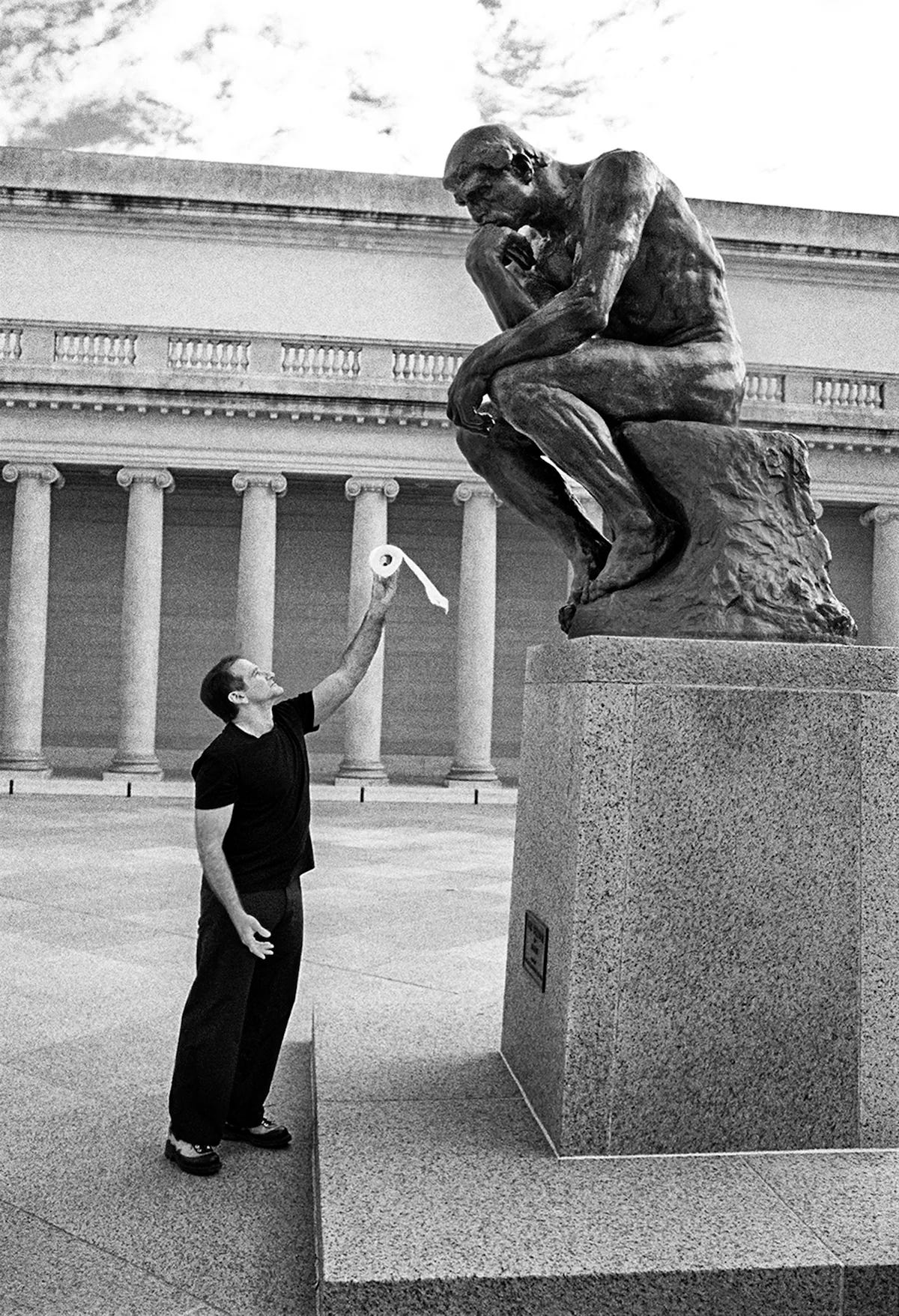

ABOVE: Robin Williams tries to help.

I haven’t been feeling myself of late. I’ve been feeling unwell. My head has felt heavy, my heart heavier still. Something is wrong with my eyes. Everything seems dark.

I worried it might be a tumor.

I worried it might be inoperable.

I worried.

I went to my doctor. She looked in my eyes, she looked in my ears. She liste…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Shalom Auslander's Fetal Position to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.