ABOVE: The author at 17, in full period mode.

I was raised by periods. My father was a period and my mother was a period. My ultra-Orthodox rabbis were periods, and the books they taught me from were periods, too. Everything was known, everything was certain: how the world came into being and how it was going to end, who the good people were and who the bad people were, what was allowed and what was forbidden, who God loved and who God hated.

God, of course, was an exclamation point.

An exclamation point is a period who yells and screams when their periods are challenged. Fascists are exclamation points. CEOs, too.

And so, eventually, I became a period.

It was nice being a period. It was comfortable and it was comforting. The calming finality of it, the warm surety: I knew what was what, I knew the score, I knew the answers. The more of a period I became, the more the periods around me approved, and so I became the periodist period of them all. I knew the answers. I had no questions. Other people in other communities had different answers than mine, answers they were certain of, too. But I was certain they were wrong. Period.

It wasn’t long before I became an exclamation point. This is not uncommon. An exclamation point, after all, is a frustrated period, a period that is being challenged, a period who isn’t being heard. Visually it’s a line, an arrow, pointing you to the period below it, in case you missed it.

And so I did what exclamation points do: I disapproved. I disdained. I sturmed and I dranged.

It was no fun. Exclamation points won’t admit it (they’re periods, after all, and periods don’t like admitting anything) but being an exclamation point is kind of a drag. It’s a bummer. There is a lot of anger involved, which is exhausting. There’s a lot of frowning and fist-making and teeth-clenching. Moreover, success is generally rare. There’s just so much exclaiming an exclamation point can do; after that, all he can do is add even more exclamation points (!!!!!) which only serves to reveal his impotence. Left unchecked, the exclamation point soon turns to ALL CAPS, the rubber-walled asylum of preachers, madmen and billionaires.

ABOVE: Periods cheer their exclamation point.

I grew tired of being an exclamation point. I disliked myself as a period. What were we periods so afraid of, anyway? Wasn’t there more to life than picking a spot on the chessboard and insisting it was the right spot until you finally dropped dead?

At last it dawned on me that the people I liked best, alive or dead, real or fictional, were question marks.

Huck. Yossarian. Candide. Job.

Question marks ask. Question marks wonder. Not just about the world, but about themselves (much more difficult, that one). Question marks aren’t afraid of change or contradiction or being wrong. “Do I contradict myself?” a famous question mark once wrote. “Very well, then I contradict myself.”

Most importantly, they laughed (not Whitman, granted, but other question marks). Periods don’t laugh, because laughter upends, laughter doubts, laughter disrespects. Exclamation points hate laughter.

The people I loved, the friends I cherished, the writers I liked, the artists I admired, the musicians I listened to – every one of them was this wonderful, weird, squiggly question mark.

And I wanted to be one, too.

There are different theories about where the question mark comes from. One theory holds that it is meant to resemble the tail of the cat of the writer who first used it – something mysterious, something perplexing, something curious. Another suggests it was created by a certain Alcuin of York, an advisor to Charlemagne who was considered “the most learned man to be found in all the lands.” It would make me very happy indeed if that were true. It would speak well of our species if the human who had all the answers was also the one to come up with the mark of a question.

I’m tempted to say that we are living in an Age of Periods, a dark era of rampant exclamation points. It’s difficult at times not to think so.

But perhaps that’s just the period in me talking.

Perhaps the truth is we’re all capable of being one mark or the other, at different times, and in different ways. If there are more periods, maybe it’s just because being a question mark is so much more difficult.

Not knowing is harder than knowing.

Uncertainty is more challenging than certainty.

But it’s worth it, trust me. As someone who’s been all three punctuations, again and again, over many years and over the course of today alone, I can tell you this: question marks have more fun. Period.

And if you’re not having fun, said Groucho Marx, you’re doing something wrong.

Yours in the fetal position,

S.

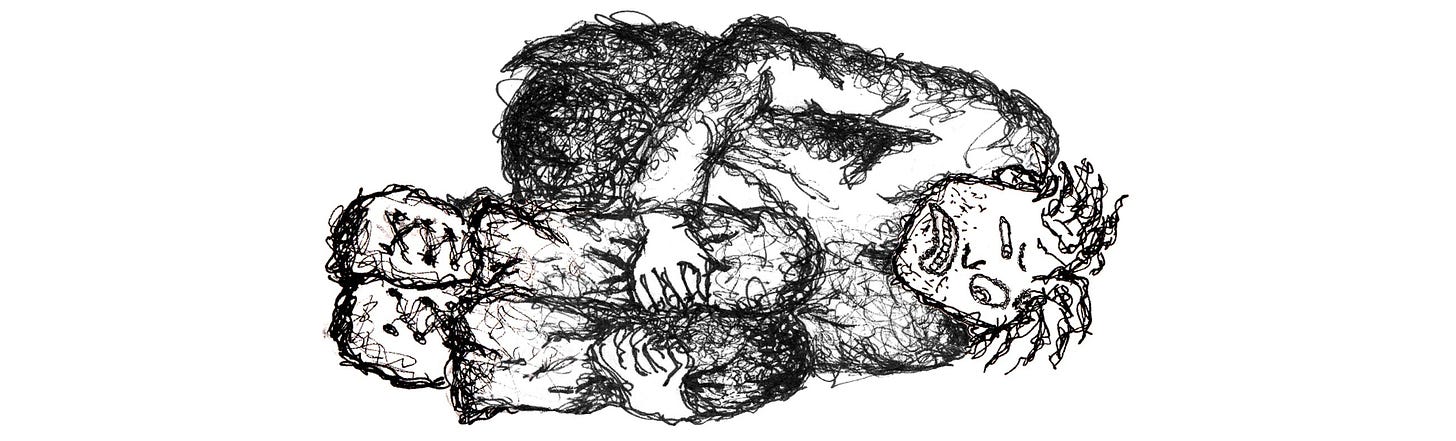

ABOVE: Just a couple of question marks question marking around (Groucho Marx and George Carlin, c. 1971)

illustrations by orli auslander

I was raised Southern Baptist; there, in the unforgiving sweat of the South, we call the periods "sheep", and Jesus is the shepherd. Jesus tends to his flock, feeds and protects them.

But are shepherds ever altruistic? They fleece sheep, milk them, force them to go wherever they deem suitable, and butcher then for meat as they please. I have never known a better metaphor for many (not all) religious leaders.

In middle school, after a particularly "fire and brimstone" preacher roared at us, on a very fine Sunday that would have been better spent not glued to a sweaty yellow pew, that no matter what we did after, we were nevertheless doomed to the suffering of Hell, and I thought then, "Then why am I wasting my time with YOU?" and I thus became a question mark.

And have been one ever since. But I never considered that leaning in grammatical terms until I read this, so I thank you. Keep being a question mark. Perhaps being so isn't always happy, and it can be lonely, but I have zero regrets, as I'm assured you must feel.

A question mark is an evolved exclamation point. It has grown, lost its rigidity, curved and grew.