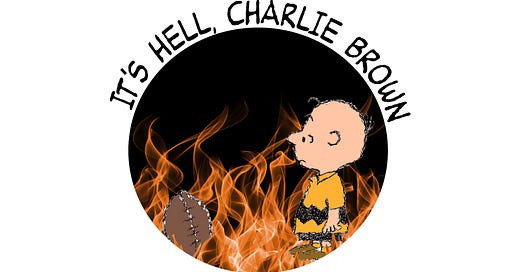

Kafka (in The Trial) did not want to write “a fairly witty fantasy"… he wanted to go down into the dark depths of a joke. – Milan Kundera

Chapter 1.

Good grief.

That was the very last thought that crossed Charlie Brown's mind as the streaking baseball slammed into his throat, two inches above the suprasternal notch, flipping him upside down into the air…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Shalom Auslander's Fetal Position to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.